Spoken language identification with deep convolutional networks

Recently TopCoder announced a contest to identify the spoken language in audio recordings. I decided to test how well deep convolutional networks will perform on this kind of data. In short I managed to get around 95% accuracy and finished at the 10th place. This post reveals all the details.

Contents

- Dataset and scoring

- Preprocessing

- Network architecture

- Data augmentation

- Ensembling

- What we learned from this contest

- Unexplored options

Dataset and scoring

The recordings were in one of the 176 languages. Training set consisted of 66176 mp3 files,

376 per language, from which I have separated 12320 recordings for validation

(Python script is available on GitHub).

Test set consisted of 12320 mp3 files. All recordings had the same length (~10 sec)

and seemed to be noise-free (at least all the samples that I have checked).

Score was calculated the following way: for every mp3 top 3 guesses were uploaded in a CSV file.

1000 points were given if the first guess is correct,

400 points if the second guess is correct and 160 points if the third guess is correct.

During the contest the score was calculated only on 3520 recordings from the test set.

After the contest the final score was calculated on the remaining 8800 recordings.

Preprocessing

I entered the contest just 14 days before the deadline, so didn’t have much time to investigate audio specific techniques. But we had a deep convolutional network developed few months ago, and it seemed to be a good idea to test a pure CNN on this problem. Some Google search revealed that the idea is not new. The earliest attempt I could find was a paper by G. Montavon presented in NIPS 2009 conference. The author used a network with 3 convolutional layers trained on spectrograms of audio recordings, and the output of convolutional/subsampling layers was given to a time-delay neural network.

I found a Python script

which creates a spectrogram of a wav file. I used mpg123 library

to convert mp3 files to wav format.

The preprocessing script is available on GitHub.

Network architecture

I took the network architecture designed for the Kaggle’s diabetic retinopathy detection contest. It has 6 convolutional layers and 2 fully connected layers with 50% dropout. Activation function is always ReLU. Learning rates are set to be higher for the first convolutional layers and lower for the top convolutional layers. The last fully connected layer has 176 neurons and is trained using a softmax loss.

It is important to note that this network does not take into account the sequential characteristics of the audio data. Although recurrent networks perform well on speech recognition tasks (one notable example is this paper by A. Graves, A. Mohamed and G. Hinton, cited by 272 papers according to the Google Scholar), I didn’t have time to learn how they work.

I trained the CNN on Caffe with 32 images in a batch, its description in Caffe prototxt format is available here.

| Nr | Type | Batches | Channels | Width | Height | Kernel size / stride |

| 0 | Input | 32 | 1 | 858 | 256 | |

| 1 | Conv | 32 | 32 | 852 | 250 | 7x7 / 1 |

| 2 | ReLU | 32 | 32 | 852 | 250 | |

| 3 | MaxPool | 32 | 32 | 426 | 125 | 3x3 / 2 |

| 4 | Conv | 32 | 64 | 422 | 121 | 5x5 / 1 |

| 5 | ReLU | 32 | 64 | 422 | 121 | |

| 6 | MaxPool | 32 | 64 | 211 | 60 | 3x3 / 2 |

| 7 | Conv | 32 | 64 | 209 | 58 | 3x3 / 1 |

| 8 | ReLU | 32 | 64 | 209 | 58 | |

| 9 | MaxPool | 32 | 64 | 104 | 29 | 3x3 / 2 |

| 10 | Conv | 32 | 128 | 102 | 27 | 3x3 / 1 |

| 11 | ReLU | 32 | 128 | 102 | 27 | |

| 12 | MaxPool | 32 | 128 | 51 | 13 | 3x3 / 2 |

| 13 | Conv | 32 | 128 | 49 | 11 | 3x3 / 1 |

| 14 | ReLU | 32 | 128 | 49 | 11 | |

| 15 | MaxPool | 32 | 128 | 24 | 5 | 3x3 / 2 |

| 16 | Conv | 32 | 256 | 22 | 3 | 3x3 / 1 |

| 17 | ReLU | 32 | 256 | 22 | 3 | |

| 18 | MaxPool | 32 | 256 | 11 | 1 | 3x3 / 2 |

| 19 | Fully connected | 20 | 1024 | |||

| 20 | ReLU | 20 | 1024 | |||

| 21 | Dropout | 20 | 1024 | |||

| 22 | Fully connected | 20 | 1024 | |||

| 23 | ReLU | 20 | 1024 | |||

| 24 | Dropout | 20 | 1024 | |||

| 25 | Fully connected | 20 | 176 | |||

| 26 | Softmax Loss | 1 | 176 |

Hrant suggested to try the ADADELTA solver.

It is a method which dynamically calculates learning rate for every network parameter, and the

training process is said to be independent of the initial choice of learning rate. Recently it

was implemented in Caffe.

In practice, the base learning rate set in the Caffe solver did matter. At first I tried to use 1.0

learning rate, and the network didn’t learn at all. Setting the base learning rate to 0.01

helped a lot and I trained the network for 90 000 iterations (more than 50 epochs).

Then I switched to 0.001 base learning rate for another 60 000

iterations. The solver is available here.

Not sure why the base learning rate mattered so much at the early stages of the training.

One possible reason could be the large learning rate coefficients on the lower convolutional layers.

Both tricks (dynamically updating the learning rates in ADADELTA and large learning rate coefficients)

aim to fight the gradient vanishing problem, and maybe their combination is not a very good idea.

This should be carefully analysed.

|

|---|

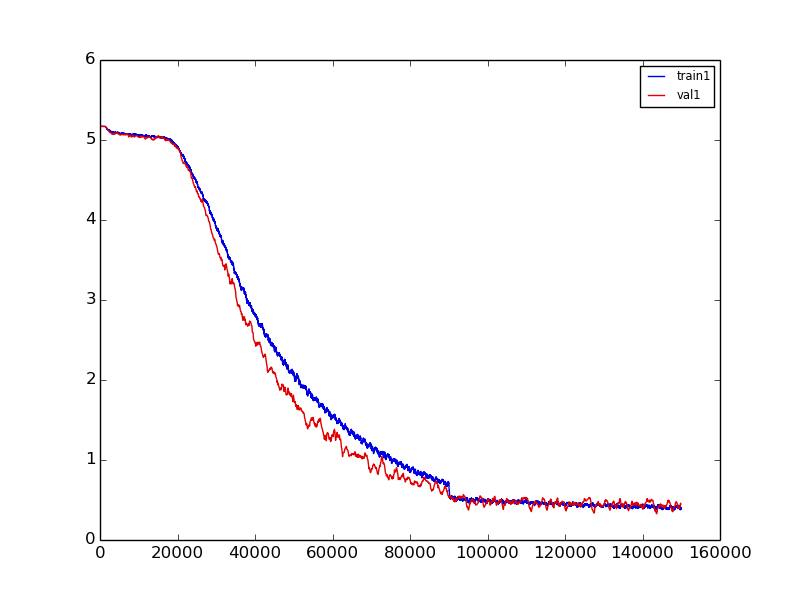

Training (blue) and validation (red) loss over the 150 000 iterations on the non-augmented dataset. The sudden drop of training loss corresponds to the point when the base learning rate was changed from 0.01 to 0.001. Plotted using this script. |

The signs of overfitting were getting more and more visible and I stopped at 150 000 iterations. The softmax loss got to 0.43 and it corresponded to 3 180 000 score (out of 3 520 000 possible). Some ensembling with other models of the same network allowed to get a bit higher score (3 220 000), but it was obvious that data augmentation is needed to overcome the overfitting problem.

Data augmentation

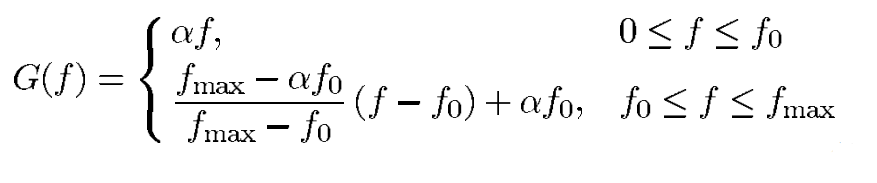

The most important weakness of our team in the previous contest was that we didn’t augment the dataset well enough. So I was looking for ways to augment the set of spectrograms. One obvious idea was to crop random, say, 9 second intervals of the recordings. Hrant suggested another idea: to warp the frequency axis of the spectrogram. This process is known as vocal tract length perturbation, and is generally used for speaker normalization at least since 1998. In 2013 N. Jaitly and G. Hinton used this technique to augment the audio dataset. I used this formula to linearly scale the frequency bins during spectrogram generation:

|

|---|

| Frequency warping formula from the paper by L. Lee and R. Rose. α is the scaling factor. Following Jaitly and Hinton I chose it uniformly between 0.9 and 1.1 |

I also randomly cropped

the spectrograms so they had 768x256 size. Here are the results:

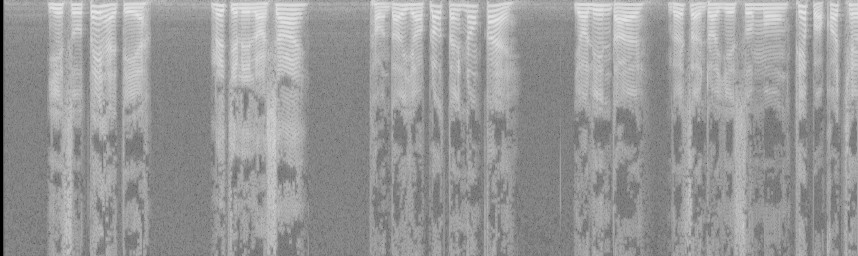

|

| Spectrogram of one of the recordings |

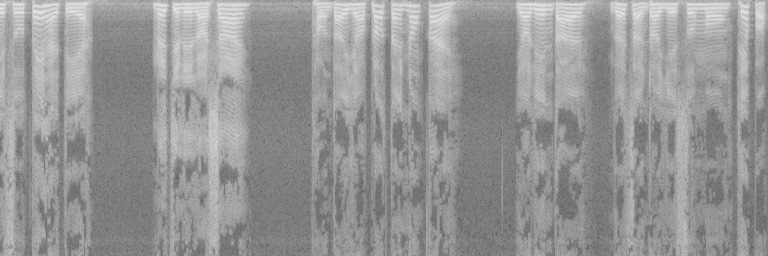

|

| Cropped spectrogram of the same recording with warped frequency axis |

For each mp3 I have created 20 random spectrograms, but trained the network on 10 of them.

It took more than 2 days to create the augmented dataset and convert it to LevelDB format (the format Caffe suggests).

But training the network proved to be even harder. For 3 days I couldn’t significantly decrease

the train loss. After removing the dropout layers the loss started to decrease but it would take weeks

to reach reasonable levels. Finally, Hrant suggested to try to reuse the weights of the

model trained on the non-augmented dataset. The problem was that due to the cropping,

the image sizes in the two datasets were different. But it turned out that convolutional

and pooling layers in Caffe work with images of variable sizes,

only the fully connected layers couldn’t reuse the weights from the first model.

So I just renamed the FC layers

in the prototxt file and initialized

the network (convolution filters) by the weights of the first model:

./build/tools/caffe train --solver=solver.prototxt --weights=models/main_32r-2-64r-2-64r-2-128r-2-128r-2-256r-2-1024rd0.5-1024rd0.5_DLR_72K-adadelta0.01_iter_153000.caffemodelThis helped a lot. I used standard stochastic gradient descent (inverse decay learning rate policy)

with base learning rate 0.001 for 36 000 iterations (less than 2 epochs), then increased

the base learning rate to 0.01 for another 48 000 iterations (due to the inverse decay policy

the rate decreased seemingly too much).

These trainings were done without any regularization techniques,

weight decay or dropout layers, and there were clear signs of overfitting. I tried to add 50%

dropout layers on fully connected layers, but the training was extremely slow. To improve the

speed I used 30% dropout, and trained the network for 120 000 more iterations using this solver.

Softmax loss on the validation set reached 0.21 which corresponded to 3 390 000 score.

The score was calculated by averaging softmax outputs over 20 spectrograms of each recording.

Ensembling

30 hours before the deadline I had several models from the same network. And even simple ensembling (just the sum of softmax activations of different models) performed better than any individual model. Hrant suggested to use XGBoost, which is a fast implementation of gradient boosting algorithm and is very popular among Kagglers. XGBoost has a good documentation and all parameters are well explained.

To perform the ensembling I was creating a CSV file containing softmax activations (or the average of softmax activations among 20 augmented versions of the same recording) using this script. Then I was running XGBoost on these CSV files. The submission file (which was requested by TopCoder) was generated using this script.

I also tried to train a simple neural network with one hidden layer on the same CSV files. The results were significantly better than with XGBoost.

The best result was obtained by ensembling the following two models: snapshots of the last network (the one with 30% dropout) after 90 000 iterations and 105 000 iterations. Final score was 3 401 840 and it was the 10th result of the contest.

What we learned from this contest

This was a quite interesting contest, although too short when compared with Kaggle’s contests.

- Plain, AlexNet-like convolutional networks work quite well for fixed length audio recordings

- Vocal tract length perturbation works well as an augmentation technique

- Caffe supports sharing weights between convolutional networks having different input sizes

- Single layer neural network sometimes performs better than XGBoost for ensembling (although I had just one day to test the both)

Unexplored options

- It is interesting to see if a network with 50% dropout layers will improve the accuracy

- Maybe larger convolutional networks, like OxfordNet will perform better. They require much more memory, and it was risky to play with them under a tough deadline

- Hybrid methods combining CNN and Hidden Markov Models should work better

- We believe it is possible to squeeze more from these models with better ensembling methods

- Other contestants report better results based on careful mixing of the results of more traditional techniques, including n-gram and Gaussian Mixture Models. We believe the combination of these techniques with the deep models will provide very good results on this dataset

One important issue is that the organizers of this contest do not allow to use the dataset outside the contest. We hope this decision will be changed eventually.