Implementing Dynamic memory networks

The Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence has organized a 4 month contest in Kaggle on question answering. The aim is to create a system which can correctly answer the questions from the 8th grade science exams of US schools (biology, chemistry, physics etc.). DeepHack Lab organized a scientific school + hackathon devoted to this contest in Moscow. Our team decided to use this opportunity to explore the deep learning techniques on question answering (although they seem to be far behind traditional systems). We tried to implement Dynamic memory networks described in a paper by A. Kumar et al. Here we report some preliminary results. In the next blog post we will describe the techniques we used to get to top 5% in the contest.

Contents

bAbI tasks

The questions of this contest are quite hard, they not only require lots of knowledge in natural sciences, but also abilities to make inferences, generalize the concepts, apply the general ideas to the examples and so on. The methods based on deep learning do not seem to be mature enough to handle all of these difficulties. On the other hand these questions have 4 answer candidates. That’s why, as was noted by Dr. Vorontsov, simple search engine indexed on lots of documents will perform better as a question answering system than any “intelligent” system.

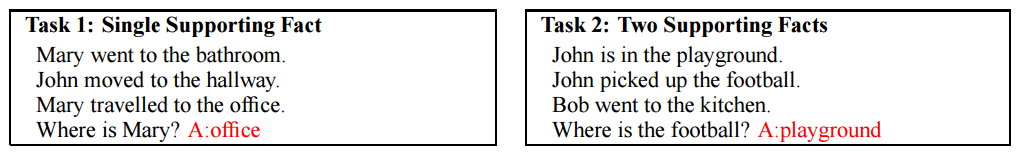

But there is already some work on creating question answering / reasoning systems using neural approaches. As another lecturer of the DeepHack event, Tomas Mikolov, told us, we should start from easy, even synthetic questions and try to gradually increase the difficulty. This roadmap towards building intelligent question answering systems is described in a paper by Facebook researchers Weston, Bordes, Chopra, Rush, Merriënboer and Mikolov, where the authors introduce a benchmark of toy questions called bAbI tasks which test several basic reasoning capabilities of a QA system.

Questions in the bAbI dataset are grouped into 20 types, each of them has 1000 samples for training and another 1000 samples for testing. A system is said to have passed a given task, if it correctly answers at least 95% of the questions in the test set. There is also a version with 10K samples, but as Mikolov told during the lecture, deep learning is not necessarily about large datasets, and in this setting it is more interesting to see if the systems can learn answering questions by looking at a few training samples.

|

|---|

|

| Some of the bAbI tasks. More examples can be found in the paper. |

Memory networks

bAbI tasks were first evaluated on an LSTM-based system, which achieve 50% performance on average and do not pass any task. Then the authors of the paper try Memory Networks by Weston et al. It is a recurrent network which has a long-term memory component where it can learn to write some data (the input sentences) and read them later.

bAbI tasks include not only the answers to the questions but also the numbers of those sentences which help answer the question. This information is taken into account when training MemNN, they not only get the correct answers but also an information about which input sentences affect the answer. Under this so called strongly supervised setting “plain” Memory networks pass 7 of the 20 tasks. Then the authors apply some modifications to them and pass 16 tasks.

|

|---|

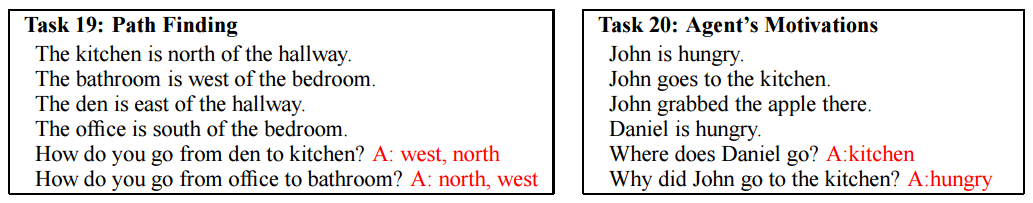

| The structure of MemN2N from the paper. |

We are mostly interested in weakly supervised setting, because the additional information on important sentences is not available in many real scenarios. This was investigated in a paper by Sukhbaatar, Szlam, Weston and Fergus (from New York University and Facebook AI Research) where they introduce End-to-end memory networks (MemN2N). They investigate many different configurations of these systems and the best version passes 9 tasks out of 20. Facebook’s MemN2N repository on GitHub lists some implementations of MemN2N.

Dynamic memory networks

Another advancement in the direction of memory networks was made by Kumar, Irsoy, Ondruska, Iyyer, Bradbury, Gulrajani and Socher from Metamind. By the way, Richard Socher is the author of an excellent course on deep learning and NLP at Stanford, which helped us a lot to get into the topic. Their paper introduces a new system called Dynamic memory networks (DMN) which passes 18 bAbI tasks in the strongly supervised setting. The paper does not talk about weakly supervised setting, so we decided to implement DMN from scratch in Theano.

|

|---|

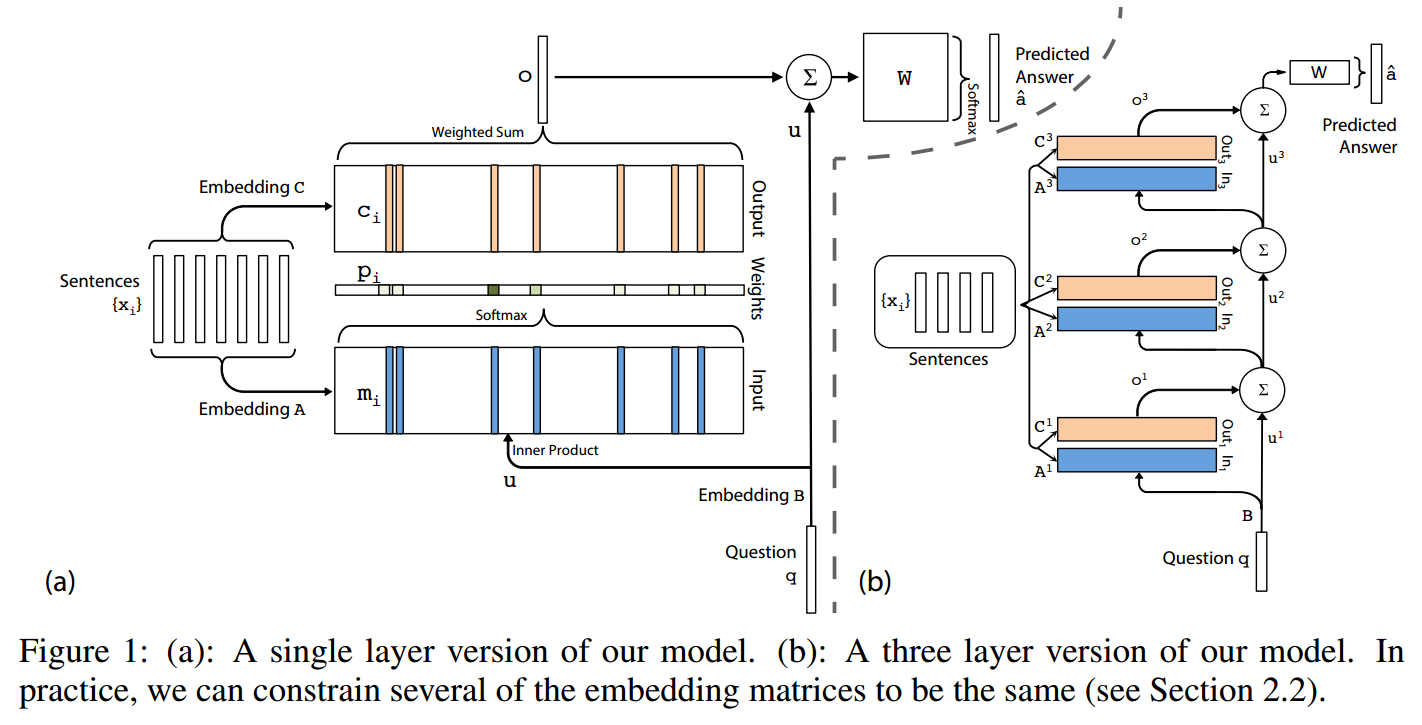

| High-level structure of DMN from the paper. |

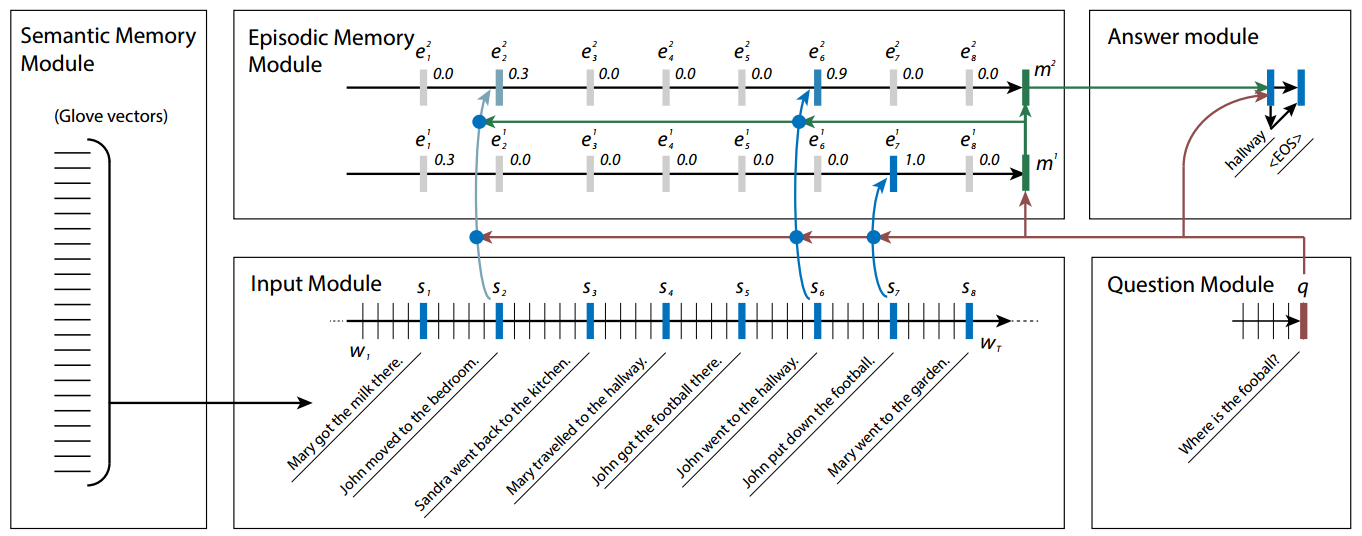

Semantic memory

The input of the DMN is a sequence of word vectors of input sentences. We followed the paper and used pretrained GloVe vectors and added the dimensionality of word vectors to the list of hyperparamaters (controlled by the command line argument --word_vector_size). DMN architecture treats these vectors as part of a so called semantic memory (in contrast to the episodic memory) which may contain other knowledge as well. Our implementation uses only word vectors and does not fine tune them during the training, so we don’t consider it as a part of the neural network.

Input module

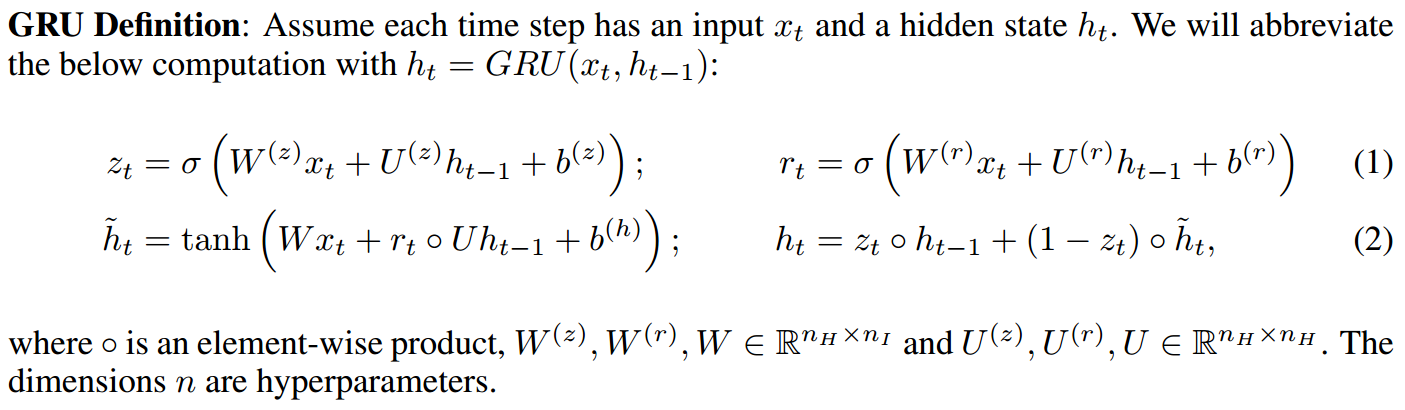

The first module of DMN is an input module that is a gated recurrent unit (GRU) running on the sequence of word vectors. GRU is a recurrent unit with 2 gates that control when its content is updated and when its content is erased. The hidden state of the input module is meant to represent the input processed so far in a vector. Input module outputs its hidden states either after every word (--input_mask word) or after every sentence (--input_mask sentence). These outputs are called facts.

|

|---|

Formal definition of GRU. z is the update gate and r is the reset gate. More details and images can be found here. |

Then there is a question module that processes the question word by word and outputs one vector at the end. This is done by using the same GRU as in the input module using the same weights.

Episodic memory

The fact and question vectors extracted from the input enter the episodic memory module. Episodic memory is basically a composition of two nested GRUs. The outer GRU generates the final memory vector working over a sequence of so called episodes. This GRU state is initialized by the question vector. The inner GRU generates the episodes.

|

|---|

| Details of DMN architecture from the paper. |

The inner GRU generates the episodes by passing over the facts from the input module. But when updating its inner state, the GRU takes into account the output of some attention function on the current fact. Attention function gives a score (between 0 and 1) to each of the fact, and GRU (softly) ignores the facts having low scores. Attention function is a simple 2 layer neural network depending on the question vector, current fact, and current state of the memory. After each full pass on all facts the inner GRU outputs an episode which is fed into the outer GRU which on its turn updates the memory. Then because of the updated memory the attention may give different scores to the facts. So new episodes can be created. The number of steps of the outer GRU, that is the number of the episodes, can be determined dynamically, but we fix it to simplify the implementation. It is configured by --memory_hops setting.

All facts, episodes and memories are in the same n-dimensional space, which is controlled by the command line argument --dim. Inner and outer GRUs share their weights.

###

The final state of the memory is being fed into the answer module, which produces the answer. We have implemented two kinds of answer modules. First is a simple linear layer on top of the memory vector with softmax activation (--answer_module feedforward). This is useful if each answer is just one word (like in the bAbI dataset). The second kind of answer module is another GRU that can produce multiple words (--answer_module recurrent). Its implementation is half baked now, as we didn’t need it for bAbI.

The whole system is end-to-end differentiable and is trained using stochastic gradient descent. We use adadelta by default. More formulas and details of architecture can be found in the original paper. But the paper does not contain many implementation details, so we may have diverged from the original implementation.

Initial experiments

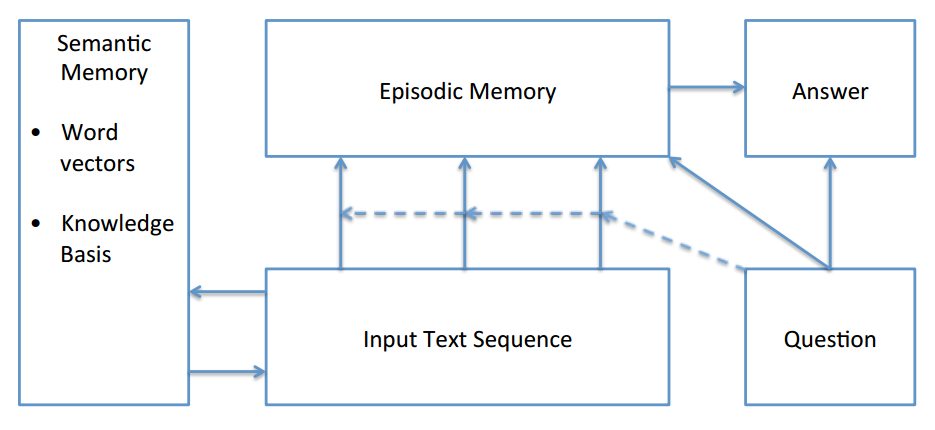

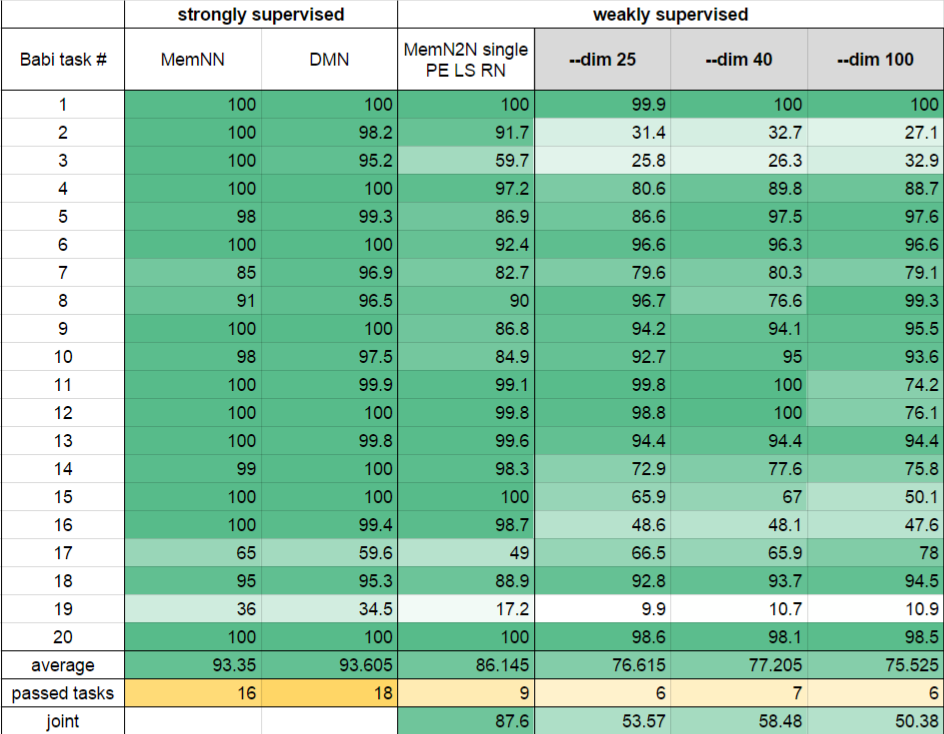

We have tested this system on bAbI tasks with a few randomly selected hyperparameters. We initialized the word vectors by using 50-dimensional GloVe vectors trained on Wikipedia. Answer module is a simple feedforward classifier over the vocabulary (which is very limited in bAbI tasks). Here are the results.

|

|---|

| First two columns are for strongly supervised systems MemNN and DMN. Third column is the best results of MemN2N. The last 3 columns are our results with different dimensions of the memory. |

First basic observation is that weakly supervised systems are generally worse than the strongly supervised ones. When compared to MemN2N, our system performs much worse on the tasks 2, 3 and 16. As a result we pass only 7 tasks out of 20. On the other hand, our results on tasks 5, 6, 8, 9, 10 and 18 are better than MemN2N. Surprisingly what we got on the 17th task is better than in strongly supervised systems!

Our system converges very fast on some of the tasks (like the first one), overfits on many other tasks and does not converge on tasks 2, 3 and 19.

19th task (path finding) is not solved by any of these systems. Wojciech Zaremba from OpenAI informed us during his lecture about one system which managed to solve it using 10K training samples. This remains a very interesting challenge for us. We need to carefully experiment with various parameters to reach some meaningful conclusions.

We have tried to test on the full shuffled list of 20000 bAbI tasks. We couldn’t reach 60% average accuracy after 50 hours of training on an Amazon instance, while MemN2N authors report 87.6% accuracy.

This implementation of DMN is available on Github. We really need lots of feedback on this code.

Next steps

- We need a good way to visualize the attention in the episodic memory. This will help us understand what is exactly going on inside the system. Many papers now include such visualizations on some examples.

- Our model overfits on many of the tasks even with 25-dimensional memory. We briefly experimented with L2 regularization but it didn’t help much (

--l2). - Currently we are working on a slightly modified architecture which will be optimized for multiple choice questions. Basically it will include one more input module which will read the answer choices and will provide another input for the attention mechanism.

- Then we will be able to evaluate our code on more complex QA datasets like MCTest.

- Training with batches is not properly implemented yet. There are several technical challenges related to the variable length of input sequences. It becomes much harder to keep in control because of this kind of bugs in Theano.

We would like to thank the organizers of DeepHack.Q&A for the really amazing atmosphere here in PhysTech.